This is a transcript of a 7 minute talk I was invited to give at the Cardiovascular and Interventional Society of Europe’s [CIRSE] annual conference in Barcelona, as part of a session on “Controversies in Standard Endovascular Aneurysm Repair [EVAR] within IFU” [indications for use].

This talk: “NICE guidelines best inform clinical practice”, was one side of a debate: my opponent’s title was “European Vascular Society [ESVS] guidelines should be the standard of care”.

If you have on-demand access to CIRSE2022 content, you can view a recording of the session here.

Barcelona. Spain. 13th September 2022. 15:00h

Thanks. My name is Chris Hammond, and I’m Clinical Director for radiology in Leeds. I was on the NICE AAA guideline development committee from 2015-2019.

I have no declarations, financial or otherwise. We’ll come onto that in a bit more detail later.

This talk is not going to be about data. I hope we are all familiar with the published evidence about AAA repair. No. This talk is about values. Specifically, the values that NICE brings to bear in its analysis and processes to create recommendations and why these values mean NICE guidelines best inform clinical practice. What are those values?

Rigour, diversity, context.

Let’s unpick those a little.

NICE’s is known for academic rigour. Before any development happens, the questions that need answering are clearly and precisely identified in a scoping exercise. A PICO question is created, the outcomes of interest defined, and the types of evidence we are prepared to accept are stipulated in advance.

The scope and research questions are then published and sent out for consultation – another vital step.

After the technical teams have done their work, their results are referred explicitly back to the scope. Conclusions and recommendations unrelated to the scope are not allowed.

This process is transparent and documented and it means committee members cannot change their mind on the importance of a subject if they do not like the evidence eventually produced.

It’s impossible to tell from the ESVS document what their guideline development process was. A few paragraphs at the beginning of the document are all we get. ESVS do not publish their scope, research questions, search strategies or results. How can we be assured therefore that their conclusions are not biased by hindsight, reinterpreting or de-emphasizing outcomes that are not expedient?

We can’t.

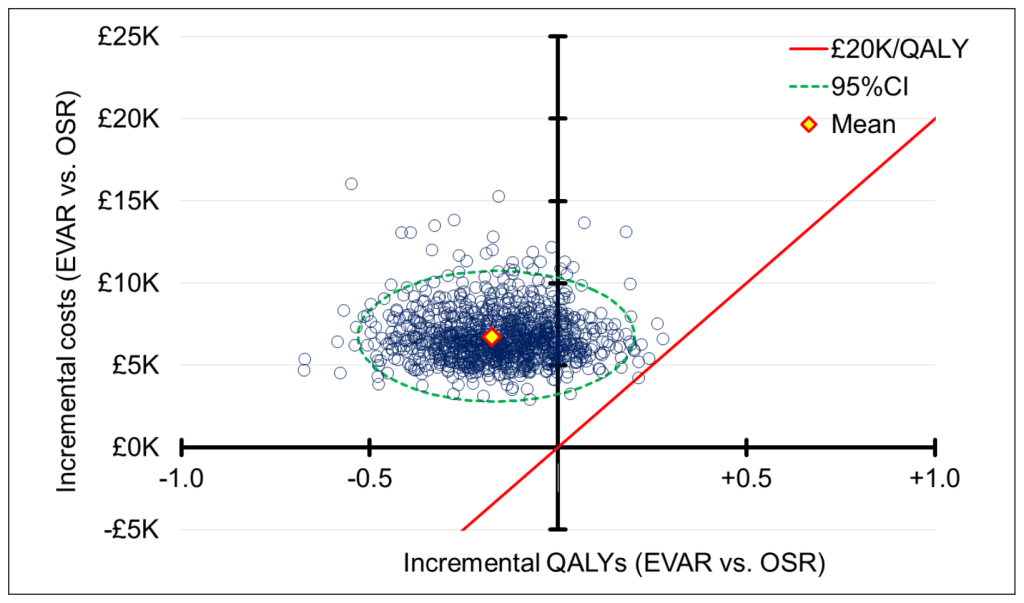

For example, data on cost effectiveness and outcomes for people unsuitable for open repair are inconvenient for EVAR enthusiasts. I’ll let you decide the extent to which these data are highlighted in the ESVS document.

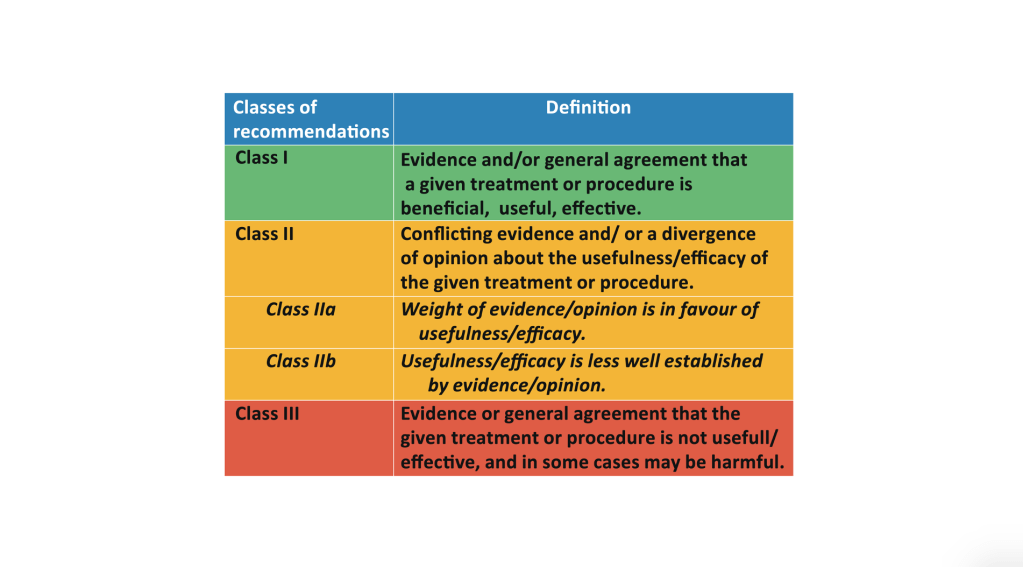

More, in failing to define the acceptable levels of evidence for specific questions ESVS ends up making recommendations based on weak data. Recommendations are made based on the European Society of Cardiology criteria which conflate evidence and opinion. Which is it? Evidence or opinion?

Opinions may be widely held and still be wrong. The sun does not orbit the earth. An opinion formulated into a guideline gives the opinion illegitimate validity.

Finally, there is the rigour in dealing with potential conflicts of interest. These are the ESVS committee declarations – which I had to ask for. The NICE declarations are in the public domain on the NICE website. Financial conflicts of interest are not unexpected though one might argue that the extensive and financially substantial relationships with industry of some of the ESVS guideline authorship do raise an eyebrow.

The question though is what to do about them. NICE has a written policy on how to deal with a conflict, including exclusion of an individual from part of the guidance development where a conflict may be substantial. This occurred during NICE’s guideline development.

The ESVS has no such policy. I know because I have asked to see it. Which makes one wonder: why collect the declarations in the first place.

How can we then be assured these conflicts of interest did not influence guideline development, consciously or subconsciously.

We can’t

What about diversity?

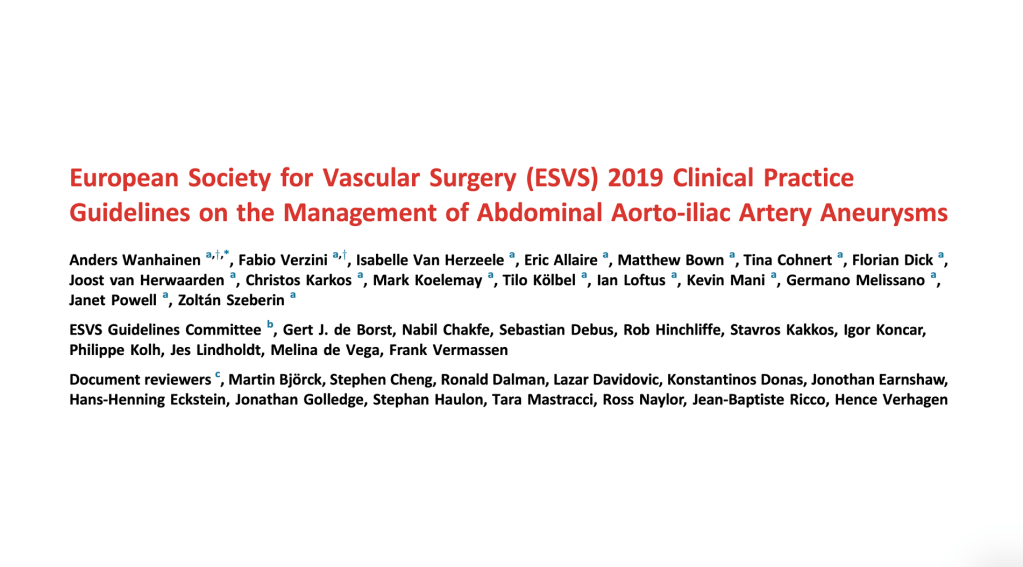

This is the author list of the ESVS guideline. All 15 of the authors, all 13 of the document reviewers and all 10 of the guideline committee are medically qualified vascular specialists. They are likely to all have had similar training, attended similar conferences and educational events and have broadly similar perspectives. It’s a monoculture.

Where are the patients in this? The ESVS asked for patient review of the plain English summaries it wrote to support its document, but patients were not involved in the development of scoping criteria, outcomes of importance or in the drafting of the guideline itself.

Where is the diversity of clinical opinion? Where are the care of the elderly specialists to provide a holistic view? Where is anaesthesia? Primary care? Nursing?

Where is the representation of the people who pay for vascular services: infrastructure, salaries, devices? And who indirectly pay for all this, maybe for your meal out last night, for the cappuccino you’ve just drunk? Where is their perspective when they also have to fund the panoply of modern healthcare?

NICE committees have representation of all these groups, and their input into the development of the AAA guidance was pivotal. The NICE guidance was very controversial, but the consistency of arguments advanced by diverse committee members with no professional vested interest was persuasive.

Finally, we come to context.

An understanding of the ethical and social context underpinning a guideline is essential.

We cannot divorce the treatments we offer from the societal context in which we operate. We live in a society which emphasises individual freedom and choice and are comfortable with some people having more choices than others, usually based on wealth. Does this apply equally in healthcare? In aneurysm care? What if offering expensive choices for aneurysm repair means we don’t spend money on social care, nursing homes, cataracts or claudicants.

To what extent should guidelines interfere with the doctor-patient relationship? Limit it or the choices on offer? What is the cost of clinical freedom and who bears it?

NICE makes very clear the social context in which it makes its recommendations. It takes a society-wide perspective, and its social values and principles are explicit. You can find them on the NICE website. Even if you don’t agree with its philosophical approach, you know what it is.

We don’t know any of this for the ESVS guideline. We don’t know how ESVS values choice over cost, the individual over the collective. Healthcare over health. This means that the ESVS guideline ends up being a technical document, written by technicians for technicians, devoid of context and wider social relevance.

The ESVS guideline is not an independent dispassionate analysis, and it never could be, because its development within an organisation so financially reliant on funding from the medical devices industry was not openly and transparently underpinned by NICE’s values of rigour, diversity and context.

Rigour. Diversity. Context

That’s why NICE guidelines best inform clinical practice.

Thanks for your attention.