Is the NHS under-resourced to deliver what is asked of it? Estimates from august think tanks and national audits describe that it is, the scale of the under-resourcing and the deficits in staffing and infrastructure created. The Darzi report identified a £11.6bn backlog in capital expenditure in the NHS in England. We have fewer beds (2.4 vs 4.3 per thousand), doctors (3.2 vs 3.7 per thousand) and scanners (19 vs 41 per million) than our OECD comparators. To keep pace with demographic changes, new technologies and drugs and the increased use of some surgical procedures, it’s estimated healthcare provision should increase 4% year on year. All OECD countries struggle with increasing healthcare spend.

Radiology services are on the sharp end of this demand growth. Imaging demand is increasing year-on-year at about 5% in the UK. For complex cross sectional imaging, demand growth was 11% in 2023 alone. Unplanned and out-of-hours imaging demand has increased 40% in 5 years. It’s rare for a clinical initiative or guideline to suggest we need less imaging, or less urgent imaging. Getting it Right First Time usually requires early imaging to make certain an uncertain clinical picture. The development of new therapies often mandates more, and more frequent, imaging. The Richards Report indicated that a 20% increase in imaging delivery was needed.

Can we control this healthcare growth? The idea of demand control in healthcare is fraught with complex ethical and moral dilemmas about access to treatment, the nature of the doctor-patient relationship and the needs of the individual versus those of the collective. The language we use (‘rationing’, ‘postcode lottery’, ‘playing God’) and powerful stories about individuals or groups denied care on the basis of decision making by ‘faceless bureaucrats’ means that rational debate about demand management in healthcare is challenging. Demand management calls into question what we mean by comprehensive healthcare and how society should respond to the needs of vulnerable people.

Even discussion about prevention and public health, effective and on-the-face-of-it uncontroversial ways to improve population health and thereby control demand long term, is freighted with unhelpful language (‘nanny statism’) and arguments about personal liberty and choice (the latter supported by powerful corporate lobbyists whose interests are risked by state interventions for smoking, alcohol and obesity). Initiatives targeting the most needy and aimed at equitable (rather than equal) resource distribution are sometimes denigrated as ‘woke’.

In the financial year 2022-23, the UK government spent £239bn on healthcare (mainly on the NHS), 18% of the total public-sector spend and 11% of GDP. At 4% growth in 10 years time this figure will be (a back of the envelope calculation) 50% greater. Healthcare spending, often protected, has already increased at the expense of other government departmental spending (especially defence – see figure) with little further room for cannibalisation of other budgets. The often advocated narrative of economic growth to deliver spending resource seems a forlorn and remote aspiration given anaemic growth figures for the UK and most other advanced economies over the last decade.

Health (green) and defence (magenta) spending as share of GDP 1955-2021

Figure source: Institute for Fiscal Studies Taxlab. What does the government spend money on?

There are undoubtedly productivity gains to be made and in radiology many potential solutions are well rehearsed: comprehensive and careful request vetting, electronic systems to support it (and to feedback to referring colleagues), decision support tools (such as iRefer) at the point of request and visibility of requests and booked scan appointments within the electronic patient record are all technical innovations that can improve a requesting culture, reduce duplication and deliver marginal reductions in demand. Skill mix and better use of radiographer reporting can help with workload and is already well established for some teams and imaging types (especially ultrasound and plain film imaging). Perhaps artificial intelligence will finally deliver its promise? Will this be enough? I doubt it.

So how can we deliver? With our current model of healthcare, ultimately, we will not be able to. The spending graphs for healthcare as a proportion of GDP extrapolate to this inevitability. Without rethinking the model, services will fail, little by little and around the edges at first in a myriad unplanned ways. The deterioration will manifest as longer waiting times and failure to meet constitutional and other standards, increases in falls, failures in infection prevention and control, loss of access for marginalised groups, estate degradation, workforce crises, increased complaints and litigation and in other, sometimes immeasurable, important ways. Does this sound familiar? It’s happening already. The irony is that as we spend more on increasingly expensive, process focussed, fractured and technology driven healthcare, we deliver less health and the experience of service users deteriorates. Healthcare delivery is more than just logistics.

We cannot address delivery without controlling demand in a systemwide manner. This especially applies to complex new therapies, imaging and drugs (which are the primary drivers of increased spending). Practical demand management is hard because we assume more healthcare equals better health, are beguiled by technology, no longer understand risk and are wedded to pathway solutions that reduce some of the intangibles of the human interaction between a patient and a healthcare professional to nodes on a decision tree from which every branch results in more to do. It is also hard because our political structures rely on promises made in a brief electoral cycle, subordinating the ability of our institutions to undertake long term planning. Complex decisions like those that are needed to equitably and ethically address demand are ignored because there will be politically unpalatable losses in the medium term while the wins may take many years to manifest.

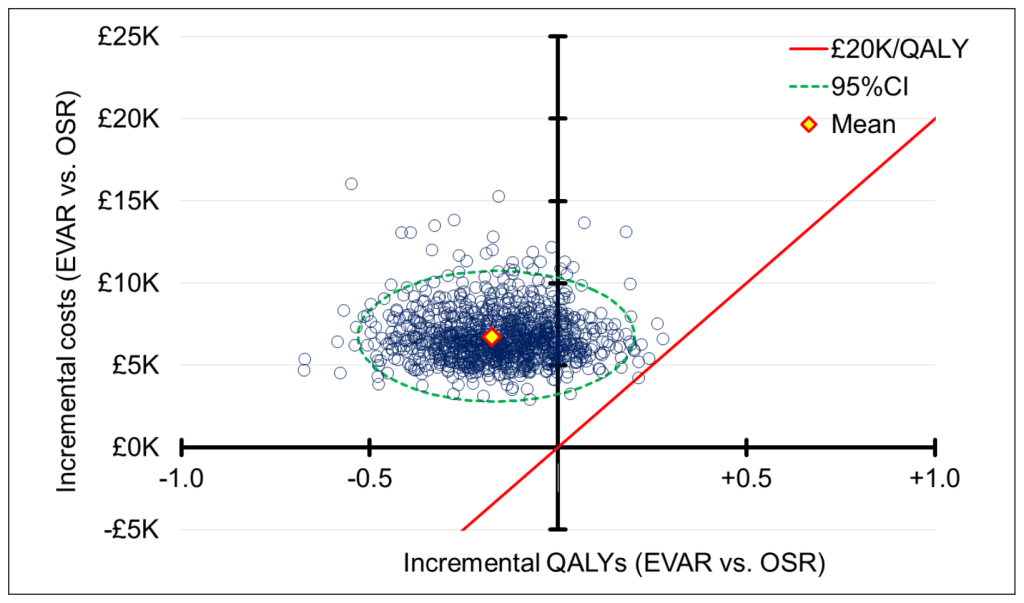

What’s the solution? A massive funding pivot to primary care and its ability to resolve many simple issues quickly, cheaply and effectively? Removing healthcare delivery from governmental control altogether, sacking the Secretary of State and assigning a fixed proportion of GDP for 25 years to allow long term planning? Addressing the social determinants of health: education, housing, lifestyle choice, opportunity, inequality? Robust implementation of cost-effectiveness principles in healthcare design? Public education about risk? Promotion of a stoic understanding of what it means to live a good life, knowing that death is inevitable?

If all that seems too far outside your zones of control or influence then perhaps in your day-to-day practice take a moment to consider the things you can change. Each time you make a decision, ask yourself: is this test, treatment, referral or innovation really needed? Who am I treating, the patient or myself? Is it easier to do the wrong thing than the right thing and if so, why? Am I too busy to think about this? Am I too proud or too anxious to ask for help? We all have a role to play in identifying pointless, wasted or supplier-induced demand. Making better small decisions every day is achievable and accumulations of hundreds of thousands of tiny marginal gains can have a big effect. This will not be sufficient on its own, but it’s necessary, vitally so.

Demand. It’s the elephant in the room of healthcare funding. Ignore it and sooner or later we’ll all be trampled. It’s our urgent responsibility as healthcare professionals to act to control demand, even if our government seems unable to.